Replying Via Twitter

Today’s Twitter rage prompts me to write about @Replies. The habit of putting an “@” symbol in front of a Twitter message, to ‘direct’ it towards another user – has a curious history. They weren’t part of the original design of Twitter, which started as a micro-blogging platform, not an instant messaging system.

As early users posted updates, they sometimes wanted to indicate that a message was directed at a specific user, or a reply to one of another user’s updates. The idea of @username was quickly adopted as the way of doing that. The @ notation has spread to other social media too – I’ve seen @name in blog comments, forums and even emails. Eventually the concept was incorporated into the Twitter system as a feature, and almost every Twitter client has an “@replies” column or a “reply” button.

Recently Twitter changed ‘replies’ to ‘mentions’ – something you can see reflected on the Twitter web interface. For me that was a retrograde step. Replies and mentions are very different, take these two tweets:

@BenjaminEllis I really don’t think that is the best answer.

Just saw @BenjaminEllis and others on BBC News today.

You can find either of them with a Twitter search, but they are semantically quite different, to my mind at least. I’m interested in the second, but probably need to respond to the first.

Yesterday Twitter went a stage further and removed a key piece of the reply functionality, which has caused an outrage on Twitter (see #fixreplies).

You would generally reply to other people, and it is tempting to think of @replies as just one type of message. They aren’t, and not just because of the mentions versus replies issue. If you take the perspective of someone who is following you, or that you follow, there are two big categories of @ reply:

- Replies to them.

- Replies to others.

Obviously you are going to be interested in replies to you – you’re on Twitter for the conversation, right? However the case of replies to others is a little more complicated, and understanding why reveals one of the most powerful aspects of Twitter.

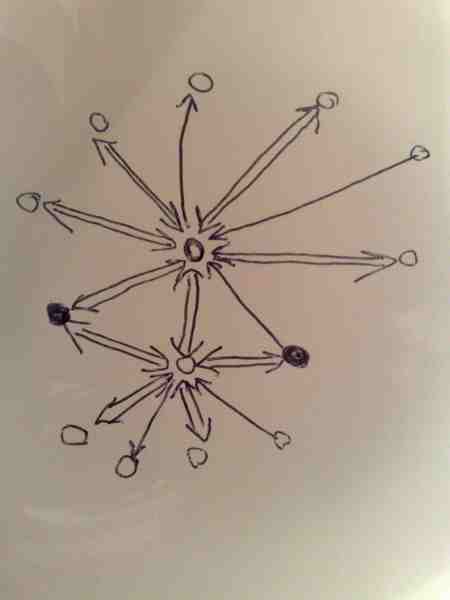

If you think of your social graph on twitter (the ‘star’ of people that you follow, and the ‘star’ of people that follow you), together with each of those people’s graphs, you’ll see something startling in the way that conversations happen on Twitter. No-one (unless they follow and are followed by exactly the same people) sees the same conversation. Pardon the crude diagram, but hopefully it helps. Think about the two users at the middle of the stars, and also the two solid dots and circles on the edge for a minute:

Everyone on Twitter sees different things, and conversations swing from people to people. It is a very unique dynamic, and one not really replicated elsewhere. Now, back to @replies. Twitter has traditionally subdivided @replies to others into two types: replies to people that you follow, and @ replies to people that you aren’t following. The reason why becomes apparent when you think about the partially-overlapping social graph each person has (that diagram above).

While it is reasonably obvious that you would want to see @replies to yourself (although you might want to see those in your timeline, or see them seperately), what to do with the others isn’t so obvious.

One argument is that you would want to see all the @ replies of the people you are following. They are part of that person’s conversation after all. This option provides a way to discover other people that you might be interested in following, or finding mutual friends that you didn’t know were on twitter. I’ve had the benefit of both of those experiences, and for me it is part of what makes Twitter a great tool: serendipity is built in.

A second argument is that seeing all of the @replies of the people you follow is going to be far too ‘noisy’ and that the only ones that are meaningful are the @ replies to people that you also follow. This is a nice halfway house, in that you can still follow conversations between your friends (or rather between the different people that you follow), but there are far fewer tweets for you to read, as you don’t get the @replies to others. The downside? Sometimes you only see half of the conversation.

In actuality, you often only see half the conversation anyway. If someone you aren’t following @replies someone that you are following, you wouldn’t normally see that tweet. According to the post on the Twitter Blog the issue of one-sided conversation fragments was their reason for removing a very useful option in Twitter: The @ replies options: Until today, Twitter allowed you to choose which argument you accepted. Via an options setting you could:

- See all @replies (ie @replies to you and all @replies sent by people you follow).

- See @replies to people that you are following (the second argument above).

- See only @replies to yourself.

This allowed a great deal of flexibility, and meant that if you were following a small number of people, you could choose to see all @replies and so gradually find new people to follow. If it all got too noisy, then you could limit what you saw down to the people that you followed, and just join in those conversations. If even that was too much, you could stick to just replies to yourself. A piece of design brilliance – leave the decision in the hands of the user. I’ll come back to that in a minute.

There is a school of thought that @replies are really just a matter between the two users involved, and that allowing people to butt into conversations is somehow wrong. From my perspective I really don’t agree with that. I quite enjoy people butting in from time to time. If the message is that private, then use a Direct Message (“D ” – although with care, one slip of the keyboard by you or the other person and that message is in the public timeline).

The issue of user choice is a tricky one for any product manager or a service designer. If you require users to make too many choices, your offering rapidly becomes hard to use, even confusing. If the choices require expertise that isn’t available to the new user, it is easy for them to get the wrong end of the stick and end up with a poor user experience.

I don’t think the @replies option has been well understood, neither have @replies in general, but I also don’t believe that is a reason to remove it. A simpler tactic (that probably wouldn’t have caused the same level of outrage in the Twitter community) would have been to change the default setting for the @replies option. It’s a neat compromise, since the ‘power users’ can still get to the setting, but those less interested in the technicalities can simply ignore it.

@EV (Twitter CEO) tweeted to say they will reconsider. Hopefully here ends the lesson, for us all. It is interesting to see a user community in action, but may also be an example of where ‘democracy’ and crowd sourcing does and doesn’t fit in with product design. I’ll come back to that one.

He’s a Qik video from a little while ago which explains more, and also shows the options that have been removed:

Great post @BenjaminEllis! Many of the people I follow (probably including you) have been found as the result of overhearing interesting conversations.

I can still see @replies containing people I don’t already follow, such as retweets or a tweet directed at multiple people that isn’t in reply to a previous tweet (i.e. #followfriday tweets).

It seems Twitter have removed the “in reply to” @replies that follow on from a previous tweet (i.e. by clicking “reply” on a tweet via the web or client, instead forming a new tweet and manually typing the recipients @name). Avoiding this would mean losing threaded conversation views, which I now find even more useful than @replies!

I didn’t realise that we had the above three options previously, and think these should definitely remain in place; and not just hidden in the setting, but also via the API to enable fast switching between the above behaviours in any client (this would be particularly useful when mobile).

Perhaps this is an indication that Twitter are removing features that could later form part of subscription-based premium accounts?

Given the vocal community response, it will be interesting to see how this one plays out!

@ahousley

It’s odd that they would see removing a feature as a step forward – surely publicising this fairly easy-to-grasp bit of twitter functionality would’ve scored more points.

What’s interesting is it’s made me think about how useful it would be for some people to be able to switch the ‘replies to people I’m following’ function on for high volume tweeters like me – I’m know there are friends of mine who choose not to follow me cos there’s to much conversation they’re not interested in (and apparently I’m the 8th highest-volume twitterer in the UK, according to techdigest.tv 🙂 )

So it would, in fact, be useful to have it even more specific, rather than less so, and then leave room for the twitter-savvy to help out the newbies. Bury it deep in a menu somewhere, so that I can tell my mates who think I tweet too much how to turn off half my stream!

Great post, sir – I love your take on things like this. Always brings clarity and context

Yes, I agree with t’other Steve. Rather than removing the option completely, they should be working to make it user specific. That would be very, very useful. The current situation is just plain dumb…

The issue, I think, is caused by inconsiderate users.

Imagine you see this in your timeline

“@BenjaminEllis yes, it’s in options.”

What is the point of that? It’s great for you to have your question (presumably) answered, but for me, it’s useless. There’s no reason why I would click to see what you two are conversing about.

I usually try to make my replies have context out of consideration for my followers. Something like

“@BenjaminEllis yes, you can set Ubuntu to foo your bars, it’s in options – settings”

Now, my followers learn something *and* may investigate you because they know you’re interested in Ubuntu and fooing your bars.

Of course, it’s not always possible to add much – or any – context. But anything that cuts down on “@BenjaminEllis LOL!” is good in my opinion.

T

You know, that’s a very good point. I’m probably very guilty of that. Must try harder:-) Not easy in 140 characters, though…

You spell it out very succinctly and graphically, Ben. I’m sure that given the response of titter users Twitter will quickly change their decision. It did give us the option before and surely it’s better to have the choice. I enjoyed finding new people that way and butting in on conversations – though it took me a while to adapt to Twitter etiquette (an evolving beast, I know).

Sometimes reading half a conversation is intriguing and stimulating and I’ve lost track on the number of times I’ve clicked on to find out what the response is to and what the other person is about. In fact I’ve met the many of the most interesting twitterers this way.

The thing I found strange is that the change was made today (according to Twitter’s blog) “to better reflect how folks are using Twitter regarding replies. Based on usage patterns and feedback”.

I wonder how extensive that was and whether it depends on how you use Twitter. Of all the people I follow I haven’t seen anything yet that is in favour of the decision but maybe that’s something about the type of people I follow – interested in Twitter as a social and sharing community.

The fact that #twitterfail and #fixreplies are such popular trends right now points to it being a wider circle of Twitter cognoscenti that feeling aggrieved though. I liked the title of the Guardain’s article:

Twitter breaks its social network: how quickly can it fix it? http://bit.ly/kP3wA

Am I the only person who finds “mentions” useful? I’d actually quite like to know if someone posted “What a load of rubbish that @jemimag writes,” for example – I mightn’t be happy, but I’d like to be aware!

…and I know there are other means of finding that out, but including mentions in the @replies column is the one that works best for me (maybe it’s easier for people without 8 zillion followers).

@Terence I believe that spamming may actually be the main reason that they took away the broader @’ing – I think a few of us have increasingly been receiving random @’s. The spammers have finally made it to Twitter.

@Alex Yes, notice that one – replies, rather than mentions, do still live on, although at the whim of the Twitter client/API – some Tweets say “in reply to…” which is key for reconstructing conversation – which is another area that is an issue. Huge opportunity for better support for conversation threading in clients. Twitter search has a nice way of reconstructing threads.

@Jemima I do find mentions useful! And I’m sure than business Twitter folk do too… I don’t have 8 zillion followers, but it is still nice (especially when mobile) to separate mentions and replies.